Introduction

Peptic ulcer is the most common and serious Gut issue many people are facing. Have you ever felt a burning pain in your stomach that won’t go away, especially between meals or at night? Many people dismiss it as simple indigestion, but it could be something more serious a peptic ulcer. In my clinical experience, I’ve met countless patients who silently suffer from ulcers, unaware of the causes, complications, or healing strategies.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll walk you through everything you need to know about peptic ulcers, from symptoms and causes to diagnosis, diet, and treatment. Whether you’re newly diagnosed or just doing your research, this article is designed to provide you with clear, reliable guidance.

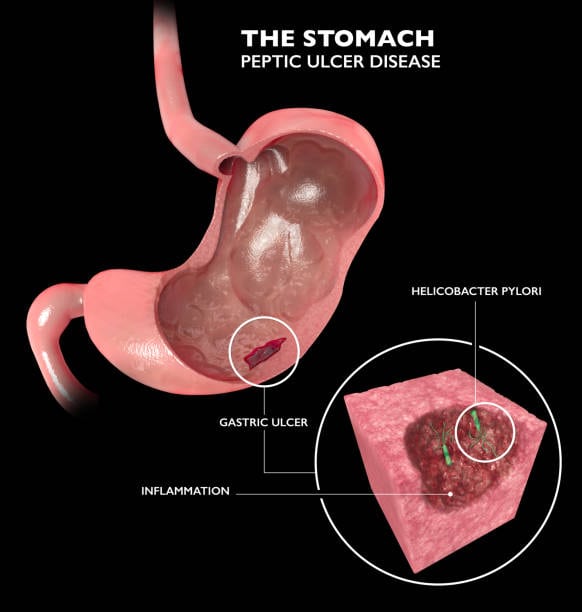

What is a peptic ulcer?

A peptic ulcer is an open sore that forms in the lining of your stomach or upper small intestine. These ulcers develop when the protective mucus layer that lines your digestive tract becomes weak, allowing stomach acids to damage the tissue.

Although it’s often confused with gastritis, which is inflammation of the stomach lining, a peptic ulcer is a deep cut or sore. (Read more about the difference between gastritis and peptic ulcers ).

Types of Peptic Ulcers

Gastric Ulcers

A gastric ulcer is an open sore that forms on the lining of the stomach. The pain, often described as a burning or gnawing sensation in the upper abdomen, usually gets worse right after eating as the stomach produces more acid. Symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and feeling full after eating a small meal are also common, sometimes leading to unintentional weight loss. Because a small percentage of gastric ulcers can lead to cancer, endoscopy with biopsy is often performed to ensure a proper diagnosis and rule out malignancy.

Duodenal ulcer

A duodenal ulcer is a peptic ulcer that develops in the first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum. Unlike gastric ulcers, the pain of a duodenal ulcer is often felt two to three hours after eating and may even wake a person from sleep, because an empty stomach allows acid to flow into the duodenum. The pain is typically relieved by eating or taking an antacid. Duodenal ulcers are almost never cancerous, which reduces the need for biopsy once the diagnosis is confirmed.

Differences between Gastric and Duodenal Ulcer.

Although the two have common causes, such as H. pylori infection and NSAID use, their clinical presentations and diagnostic considerations are significantly different. The main difference lies in the timing of the pain compared to eating: gastric ulcer pain is exacerbated by eating, while duodenal ulcer pain is usually relieved by it. Additionally, gastric ulcers require a more careful diagnostic approach because of the risk of malignancy, a concern that is largely absent with duodenal ulcers.

Causes of Peptic Ulcers

A number of factors can weaken your stomach’s defenses and lead to ulcers. Common causes of peptic ulcers include:

- Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection – This bacterium disrupts the mucus layer and is responsible for most ulcers worldwide. Johns Hopkins Medicine – Helicobacter Pylori

- Long-term use of NSAIDs (eg, ibuprofen, aspirin) – These drugs reduce the protective lining of the stomach.

- Smoking and alcohol – Increase acid production and slow healing.

- Chronic stress – While not a direct cause, stress and gastritis often go hand in hand and can make symptoms worse.

- Spicy foods and caffeine – These can irritate the lining and worsen existing ulcers.

(For more, see our post on the causes of gastritis and peptic ulcers).

Common symptoms of peptic ulcers

Many sufferers confuse ulcers with heartburn or indigestion. But knowing the symptoms of peptic ulcers can help you act quickly:

- Burning stomach pain (especially when hungry or at night)

- Nausea or vomiting

- Bloating or fullness

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Dark or tarry stools (indicating bleeding)

Seek immediate medical attention if you experience black stools or vomiting blood.

Diagnosis and Tests

If you’re experiencing symptoms of a peptic ulcer, it’s important to get a proper diagnosis. Your doctor may order several tests to confirm the presence of an ulcer, identify its cause, and rule out other conditions.

Here’s a breakdown of each test and what it involves:

1. Medical history and physical exam

Your doctor will start by asking about your:

- Symptoms (pain pattern, timing, severity)

- Use of NSAIDs or other medications

- Lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol, stress)

- Painful history of ulcers or gastritis

During the physical exam, your doctor may gently press on your abdomen to check for tenderness, bloating, or signs of internal bleeding.

2. Stool test

A stool sample is tested to detect:

- Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection – the most common cause of peptic ulcers.

- Occult (hidden) blood – which can indicate bleeding from an ulcer.

This test is non-invasive and is often used as a first-line screening method.

3. Urea breath test

This is a simple and highly accurate test to check for H. pylori.

How it works:

You will swallow a special liquid or capsule containing urea.

If H. pylori is present in your stomach, it breaks down the urea and releases carbon dioxide.

You will then exhale into a bag, and the carbon dioxide level will be measured.

This test is safe, painless, and very reliable.

4. Blood tests

Blood tests can help:

- Detect antibodies against H. pylori (although less accurate than stool or breath tests).

- Check for anemia, which can suggest internal bleeding due to a peptic ulcer.

- Monitor overall health (e.g., low hemoglobin, signs of inflammation).

Although still used, blood tests are less popular today because they cannot distinguish between past and current H. pylori infection.

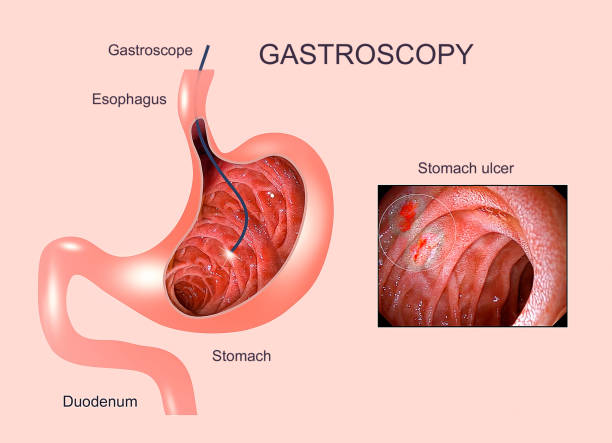

5. Upper endoscopy (Esophagogastroduodenoscopy – EGD)

This is the gold standard test for diagnosing peptic ulcers.

What to expect:

- A thin, flexible tube with a camera (endoscope) is passed through your mouth into your stomach and duodenum.

- The doctor can visually examine the lining, looking for ulcers, bleeding, inflammation, or tumors.

- A biopsy may be taken during this procedure to: Confirm H. pylori infection and Rule out stomach cancer or other diseases.

- It’s done under light sedation, so you’ll be completely comfortable.

6. Barium swallow (upper GI series)

This is a less commonly used but still valuable imaging test.

How it works:

You will drink a white, chalky liquid containing barium, which coats your digestive tract.

X-rays are then taken to show:

- Ulcers

- Narrowing

- Abnormalities or swelling

This test may be used when endoscopy is not available, or to provide additional structural information.

Natural remedies for peptic ulcers: Mayo Clinic – Peptic Ulcer Diagnosis and Treatment

Many patients ask me, “Can I heal my ulcers naturally?” While medications are key, certain natural remedies can help with healing:

- Probiotics – found in yogurt or kefir, they help keep the gut bacteria in balance.

- Honey – has antimicrobial properties.

- Green tea and garlic extract – may help fight H. pylori.

- Slippery elm and licorice root (DGL) – Create a protective coating in the stomach.

- Cabbage juice – Rich in vitamin U, promotes mucus healing.

(Discover more in our article on natural remedies for peptic ulcers).

Note: Always talk to your doctor before trying herbal remedies some may interfere with medications.

Treatment Options: Medications and Lifestyle

Medications for Peptic Ulcers

Depending on the cause, especially if H. pylori is involved, treatments include:

Medical treatment of Peptic Ulcer

Once a peptic ulcer is diagnosed, the main goals of treatment are to eliminate the cause, promote healing, and prevent complications or recurrence.

Here’s a breakdown of the commonly used medications, their typical dosages, and how long they are usually prescribed:

1. Antibiotics – To Kill H. pylori

If your ulcer is caused by H. pylori infection, your doctor will prescribe a combination of antibiotics to completely eradicate the bacteria.

Common Triple Therapy (for 14 days):

Amoxicillin – 1000 mg twice daily

Clarithromycin – 500 mg twice daily

Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) – e.g., omeprazole 20 mg twice daily

Timing: Take antibiotics after meals, and the PPI 30 minutes before meals.

Duration: 14 days, followed by continuation of PPI alone.

Alternative options:

If allergic to penicillin or resistance is suspected, metronidazole may replace amoxicillin.

2. Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) – To Reduce Acid Production

PPIs reduce stomach acid, allowing the ulcer to heal and preventing further damage.

Common PPIs and doses:

Omeprazole – 20 to 40 mg once or twice daily

Esomeprazole – 20 to 40 mg once daily

Pantoprazole – 40 mg once daily

Timing: Take 30–60 minutes before breakfast (and dinner if twice daily).

Duration: Usually continued for 4 to 8 weeks, even after antibiotics are completed.

3. H2-Receptor Blockers – Acid Reduction (Less Common Now)

These reduce acid production too, but are less potent than PPIs. They’re still used when PPIs aren’t tolerated.

Examples:

Ranitidine (withdrawn in many countries due to safety concerns)

Famotidine – 20 mg twice daily or 40 mg at bedtime

Timing: Take at bedtime or twice daily before meals.

Duration: Typically for 6 to 8 weeks.

4. Antacids – To Neutralize Stomach Acid Temporarily

Antacids offer quick, short-term relief by neutralizing existing stomach acid. They don’t heal ulcers but help reduce pain.

Common types:

Magnesium hydroxide

Aluminum hydroxide

Calcium carbonate (e.g., Tums)

Timing: Take 1–3 hours after meals and at bedtime, or as needed for pain.

Avoid using them too close to antibiotics (separate by 2 hours), as they can reduce absorption.

5. Mucosal Protective Agents – To Coat and Protect the Ulcer

These medications create a protective barrier over the ulcer, shielding it from acid and enzymes.

Most common:

Sucralfate – 1 gram four times daily or 2 grams twice daily

Timing: Take on an empty stomach, usually 1 hour before meals and at bedtime.

Duration: Often prescribed for 4 to 8 weeks, depending on severity.

Tips:

Do not take Sucralfate with antacids; allow at least 30 minutes between them.

It may cause mild constipation in some patients.

Lifestyle changes to treat gastritis and ulcers

- Avoid NSAIDs unless prescribed.

- Eat smaller, more frequent meals.

- Quit smoking and limit alcohol.

- Manage stress through yoga, meditation, or therapy.

- Follow a balanced gastritis diet rich in vegetables, lean protein, and low-acid fruits.

Signs that your ulcer is healing.

Here are some encouraging signs that your ulcer is healing:

- Less or no pain between meals.

- Improved appetite and digestion

- Less bloating and nausea

- Return to normal stool color.

- Normal endoscopy results

(Learn more about signs that your ulcer is healing).

When to see a doctor

Don’t wait for complications. See a doctor if you have:

- Persistent upper abdominal pain

- Vomiting, especially blood

- Unexplained weight loss

- Difficulty eating

- Black or tarry stools

- Family history of GI diseases

Early diagnosis prevents serious consequences such as bleeding, perforation, or stomach cancer.

Conclusion: You Can Heal

Dealing with a peptic ulcer can be uncomfortable and scarY but you’re not alone. With the right treatment, diet, and care, healing is not only possible it’s expected. As a medical professional, I’ve seen hundreds of patients recover fully with proper guidance.

And don’t forget to subscribe to our health blog for more tips on healing gastritis, managing digestive issues, and living your healthiest life.

FAQS

Diagnosis typically involves a doctor reviewing your symptoms and medical history. Tests may include a breath or stool test to check for H. pylori infection. The most definitive method is an endoscopy, where a small camera is used to view the ulcer and take a biopsy if necessary.

Treatment depends on the cause. If H. pylori is present, a combination of antibiotics and acid-reducing medications is used. If NSAIDs are the cause, discontinuing them and using acid-suppressing drugs is the main treatment. Lifestyle changes, such as avoiding spicy foods and alcohol, also help with healing.

The most common symptom is a burning or gnawing abdominal pain, typically located in the upper part of the stomach. The pain may come and go and can be worse at night. Other symptoms can include bloating, heartburn, nausea, and feeling full quickly after eating.

A peptic ulcer is an open sore that develops on the lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer), esophagus, or the upper part of the small intestine (duodenal ulcer). The most common causes are an infection with H. pylori bacteria and the long-term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

A gastric ulcer is in the stomach, and its pain often worsens with eating. A duodenal ulcer is in the small intestine, and its pain is often relieved by eating. Duodenal ulcers are also far less likely to be cancerous, unlike some gastric ulcers which require a biopsy.

🧑⚕️ About the Author

Dr. Asif, MBBS, MHPE

Dr. Asif is a licensed medical doctor and qualified medical educationist with a Master’s in Health Professions Education (MHPE) and 18 years of clinical experience. He specializes in gut health and mental wellness. Through his blogs, Dr. Asif shares evidence-based insights to empower readers with practical, trustworthy health information for a better, healthier life.

⚠️ Medical Disclaimer

This blog is intended for educational and informational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or another qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard or delay medical advice based on content you read here.

Leave a Reply